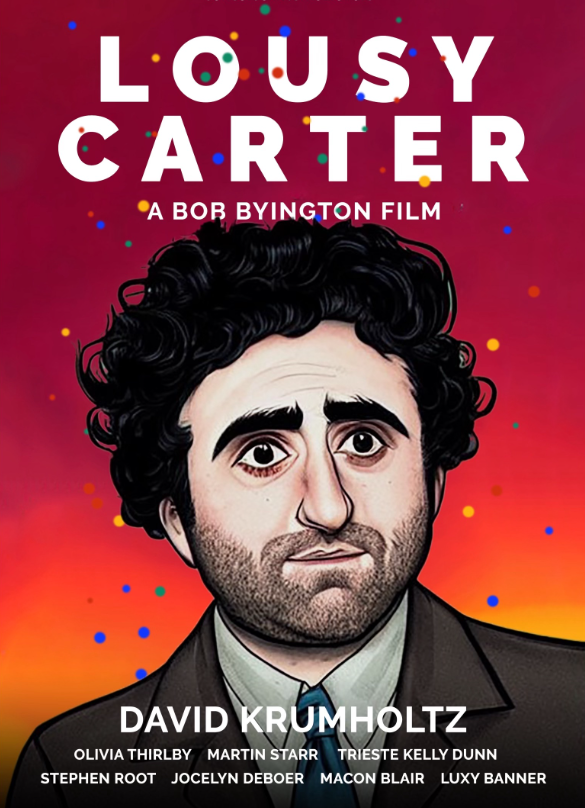

Glasgow Film Festival Interview | ‘Lousy Carter’

LAUGHING IN THE FACE OF DEATH

If you’re going to be inappropriate – you had better be funny.

Bob Byington lounges comfortably, an unwrapped but untouched chocolate bar placed neatly beside a cup of coffee. From across the table, there is a hum of psychic ennui, a laconic languor transmuted by mental acuity.

This sharpness brings into focus a heightened awareness and wit. From here, Byington’s latest film, Lousy Carter, emerges.

Throughout his career, Byington’s intelligent wit has been embodied in sardonic narratives and societal observations – and Lousy Carter is no exception. A man, told he is going to die, has no desire to right his wrongs or seek redemption. He has no interest in scrambling for a ‘do-over’, in fighting the inevitable or denying that human beings are the sum of their choices and most of the time those choices are selfish, ridiculous, or downright absurd. Facing mortality is a theme born amidst the pandemic’s uncertain gloom, where scribbled notes and isolation birthed a narrative steeped in existential introspection.

“I wrote it during the pandemic, and began with “death draws nearer” on a post it note,” Byington explains. “It’s a letter to the pandemic – in the original script there were bodies on the sidewalk, because when the pandemic hit there was this perception that it’s like a plague and people are going to be dropping dead…but that’s not in the final version.”

A (failed) animator turned literature professor, Lousy calls his ex-girlfriend with the news, who suggests that he use the opportunity to have an affair with one of his students – Gail. In a bid to entertain the idea, Lousy fills her in on a stagnated project – an animation of Vladimir Nabokov’s “Laughter in the Dark” (the irony of “Lolita” not lost here).

His journey, or lack of one, unfolds against a backdrop of literary motifs. Lousy’s only chosen class text is The Great Gatsby, a deep personal favourite of Byington’s. Green emblems are scattered throughout the film as subtle homages to the “green light that burns all night” at the end of Daisy’s dock.

“You can take any sentence in the book and try to imagine it differently and it’s almost impossible to imagine any sentence in the entire book different from what it is. I knew the students would be skeptical or slightly more disdainful of the politics of the book today, but that was like a parallel with Lousy being like a dinosaur. It’s certainly read differently now. Things weren’t questioned that are questioned now, but I wrote Gail’s criticisms and understand them. Being more aware is important.”

It isn’t just the landscape of literature that has changed, but comedy itself. Countless comedians and writers have argued that censoring and cancelling limits the creative potential, if not, point, of comedy. Navigating the contemporary comedic landscape of what can or can’t be said, Byington muses on creative boundaries, threading humour through challenging or sensitive themes.

“I’m certainly nostalgic for a looser environment – but there’s a scene where Lousy says to Gail, “I’m not attracted to you.” He’s being inappropriate with her. We determined we were going to do a scene like this – and she responds, saying, “I don’t feel safe.” But it’s funny because she’s actually sort of in control of him. Everyone was on board with it, but I think it’s easier, for me, at least, to be funny if you can be inappropriate.”

David Krumholtz, who plays Lousy, is renowned as being inherently funny – though you may think his character has nothing to laugh about at all. He infuses levity into the character in a way that is far from lousy, adding depth to seemingly sombre scenes. Byington smiles, “He’s just got this way of pulling it off perfectly.”

Byington, too, continues to execute his characteristic deadpan delivery with unique and unchallenged flawlessness seen throughout his work.

“We made a movie 15 years ago about a sex offender getting out of prison. He gets out, and everywhere he goes, he’s pilloried. To me, that’s an obvious comedic trope. And one of the central questions around it by those, who, I guess didn’t like the movie or thought it was inappropriate, was “why?”. It’s the same for me here, with a guy being diagnosed with a health problem and he only has six months to live. That presents itself to me as an opportunity to me.”

Byington’s intelligent attention to detail is precisely what makes his films affecting and amusing. So much so, that I can’t help but wonder if what people feel uncomfortable about isn’t the subject matters themselves, but the fact that our own comical bullsh*t is often on full display.

There aren’t many things that genuinely make us better people for the long term, and knowing that death is coming for us doesn’t automatically make us better either – if anything, we just get better at finding worse ways to forget about it. And so there are a multitude of characters surrounding Lousy that surprise viewers with their own questionable revelations – extramarital affairs, implied dalliances with co-eds, nods to old-world ideas of sleeping with your friends’ sister, unhealthy obsessions.

These components emerge as offshoots around Lousy’s own trajectory with entertaining surprise, a testament to how key aspects of the script unfolded, which Byington describes as “accidental”.

“I knew that Lousy was going to be diagnosed, and I knew that he would determine with the diagnosis that he was going to pursue a student, and I sort of knew he was having an affair but not consciously, and not who with. When I wrote the script, I didn’t know about the Dick Anthony character, either. It was all a kind of a surprise.”

This flow of ideas is seen in the natural progression of the narrative, characters, and their interactions and discoveries about each other (but not themselves), which creates an organic surprise in viewers too. “If the writing is dead when you’re writing it, it’s going to be dead for the audience too.”

Ultimately, Lousy Carter is a film about what it’s like to be a person. Not any particular kind of person, and not particularly kind – just a person, and how utterly absurd and funny that all is.

Mid-way through the film in a driveway garage, Lousy and his ‘best friend’ Kaminski briefly reflect on death and regret. Kaminsky turns and says, “With the abyss I see it as pointless to try, you see it as pointless not to.”

And for Byington? “I would say it’s probably pointless to try – but I’m out here trying to make movies and stuff, so…”

With Lousy Carter, Byington manages to perfectly portray that one of the most reassuring, and funny things in life, is that “death draws nearer” – for us all.

The Glasgow Film Festival runs to March 10.