In Nigerian Modernism: Art and Independence, Tate Modern undertakes a long-overdue reckoning with one of the most vital yet underrepresented movements in 20th-century art. The exhibition does not merely trace a historical arc; it maps a nation’s visual awakening. Through more than 250 works spanning painting, sculpture, ceramics, textiles, and works on paper, the show invites viewers to witness the formation of a distinctly Nigerian modernism – one forged in the crucible of colonial rule, independence, and the search for postcolonial identity.

Unlike the tidy narratives that often define European modernism, Nigeria’s modern art was never a singular movement but a chorus of distinct, sometimes discordant voices. From the early 20th century, when British colonial rule sought to define and constrain Nigerian identity, artists responded with acts of visual defiance. Figures such as Aina Onabolu and Akinola Lasekan reimagined portraiture and history painting, inserting African bodies and stories into genres long monopolized by the colonial gaze. Their work embodies both rebellion and synthesis: the mastery of imported European techniques turned against their origin, and used instead to celebrate Nigerian dignity and intellect.

Nike Davies-Okundaye, Animal World 1968Kavita Chellaram. Image courtesy of kó, Lagos © Nike Davies Okundaye

The exhibition unfolds like a series of overlapping conversations between continents. Ben Enwonwu’s sculptural grace and Ladi Kwali’s sinuous ceramics exemplify the creative fusion of Western training and Indigenous aesthetics. Enwonwu’s adaptation of Igbo sculptural form through a Slade School lens feels both subversive and celebratory, while Kwali’s ceramics, born from the cross-pollination between Gwari tradition and European studio pottery, gleam as tactile evidence of artistic diplomacy.

Independence in 1960 infuses the exhibition’s middle rooms with an air of exuberant experimentation. The Zaria Art Society – with Uche Okeke, Demas Nwoko, Yusuf Grillo, Bruce Onobrakpeya, and Jimo Akolo among its luminaries – declared a philosophy of Natural Synthesis, envisioning a modern art rooted in the soil of Nigerian heritage yet unbound by it. Their works pulse with the optimism of a new nation: geometric abstraction meets Yoruba mythology, line and pigment become acts of self-definition.#

Uzo Egonu, Will Knowledge Safeguard Freedom 2 1985 (c) Estate of Uzo Egonu. Tiana and Vikram Chellaram

This spirit of collaboration extended beyond visual art. In Ibadan, the Mbari Artists’ and Writers’ Club – a crucible of postcolonial thought that united figures like Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, and Malangatana Ngwenya – formed a radical nexus of literature, performance, and art. Tate’s inclusion of Black Orpheus, the Club’s influential journal, underscores how Nigerian modernism transcended national borders, merging Pan-African ideals with international avant-garde sensibilities.

Yet the exhibition does not romanticize the post-independence period. The devastating Nigerian Civil War of 1967 to 1970 shattered the utopian vision of unity, forcing artists to reckon with trauma, loss, and reconstruction. Here, the revival of uli – the flowing, symbolic linework of Igbo women’s body and wall painting – becomes a powerful metaphor for cultural healing. Artists of the Nsukka School, including Obiora Udechukwu, Tayo Adenaike, and Ndidi Dike, transformed these traditional motifs into modernist visual languages, reclaiming ancestral knowledge as both resistance and renewal.

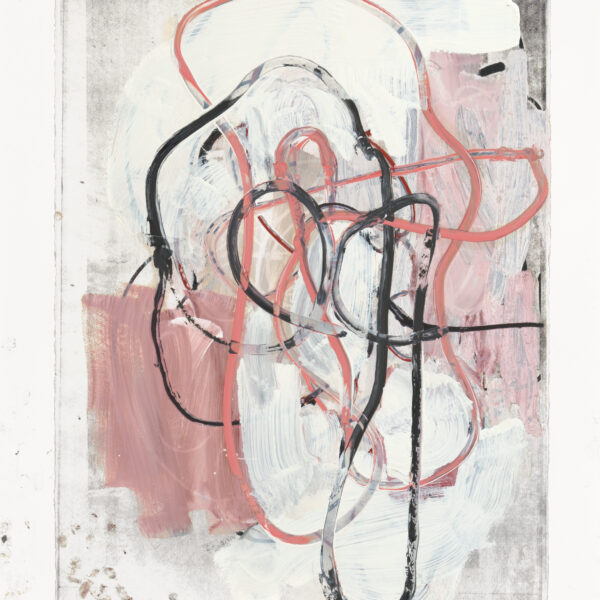

Another thread emerges in the spiritual and ecological dialogues of the New Sacred Art Movement, led by Susanne Wenger and her Yoruba collaborators in Osogbo. Their monumental cement sculptures, rising from the Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove, are part ritual, part rebellion – an affirmation of Indigenous cosmology against the flattening effects of colonial Christianity and Islam. Meanwhile, the Oshogbo Art School, born in the informal workshops of Duro Ladipo’s Popular Bar, becomes the exhibition’s heartbeat of grassroots creativity, nurturing untrained artists like Nike Davies-Okundaye and Twins Seven Seven, whose vivid, mythic compositions radiate joy and self-possession.

Uzo Egonu, Stateless People an artist with beret 1981. (c) The estate of Uzo Egonu. Private Collection.

The final room centers on Uzo Egonu, whose Stateless People series (1980) offers a poignant coda. Having lived in Britain since the 1940s, Egonu paints figures adrift between homelands – musicians, writers, artists – each emblematic of a global Nigerian identity both fractured and fertile. His work captures the paradox of modernism itself: rooted yet restless, national yet universal.

Nigerian Modernism: Art and Independence is, in the end, less an exhibition than a reclamation. It dismantles the notion that modernism was born in Paris or London and later “arrived” in Africa; rather, it asserts that Nigerian artists were co-authors of modernity, reimagining its forms through the lens of liberation. In this gathering of visions – from Lagos to London, Osogbo to Nsukka – we see modern art not as a Western export, but as a global dialogue shaped by Nigeria’s unyielding pursuit of artistic and political freedom.

It is a story of independence not only from empire, but from the very boundaries of art history itself.

Header: Ben Enwonwu, The Dancer (Agbogho Mmuo – Maiden Spirit Mask) 1962 © Ben Enwonwu Foundation, courtesy Ben Uri Gallery & Museum