Maya Balcioglu | Medusa

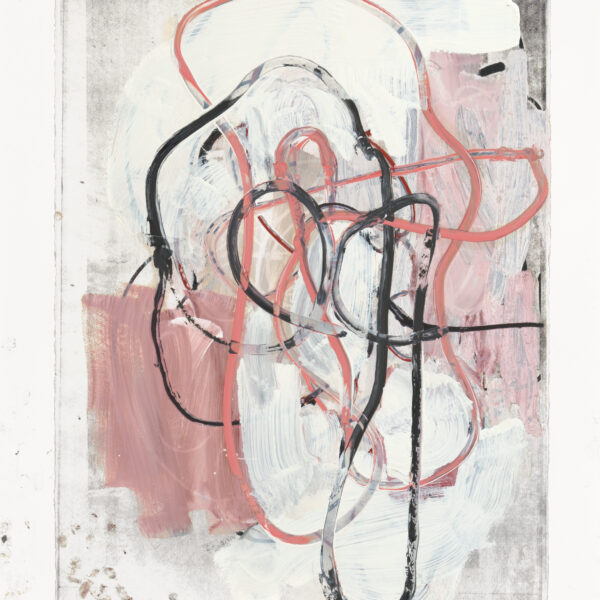

On the question of women in Ancient Greece there’s often a crystallisation around a centre, that of mania.

This takes many forms but perhaps most strikingly in acts of dismemberment and decapitation when women are in trancelike states (here I’m thinking of Dionysus and the Maenads).

Plato says poetry is a form of mania (divine inspiration or possession) and poets said to speak by divine power. It follows therefore that poets cannot have knowledge of what they write or able to explain the meaning of what they do.

The poet is simply the mouthpiece of the gods, like the Delphic priestess, and writes as it were a dictation.

A condition of askesis, naked singularity and unity of impulse, it is also a central Sufi concept in Islamic theology, a rupture or transitional spiritual state which is not stable by itself (Hal).

This is why for example in Sufism we find the practice of systemic self examination as a counterpoint (Muhasaba).

When I travelled with the Berbers in the Atlas Mountains I came across women wearing headdresses similar to depictions of the Medusa.

These were worn to ward off violence. Berber women also take part in a trancelike dance called Guedra where the head of the dancer is not revealed.

Herodotus says that Medusa (the only mortal of the Gorgon sisters) was born in Libya and that when Perseus decapitated her to present her head to jealous Athena he flew over North Africa. Medusa’s blood dripped onto the Libyan desert, where we now find oil which is so pure it hardly needs refining.

We know not much about place of women in Attic civil society. What we do know is mostly what they were forbidden to do.

We also know that the Attic culture was not so much involved with aesthetics as we may now experience a work of art, but it was a question

of aesthetic regime as political discourse.

This is why tragedy remains central.

-Maya Balcioglu