Ithell Colquhoun | Tate Britain

The first major exhibition of surrealist Ithell Colquhoun is now open at Tate Britain.

Tate’s new exhibition devoted to Ithell Colquhoun (1906–1988) is nothing short of a revelation. Long sidelined in the history of British Surrealism, Colquhoun emerges here not only as a painter of formidable imagination but as a visionary thinker whose work bridged art, mysticism, ecology, and sexuality with rare conviction. With over 170 works and archival materials brought together — many never before exhibited — this survey offers the most comprehensive account to date of her restless, shape-shifting practice.

The exhibition unfolds chronologically, beginning with Colquhoun’s years at the Slade School of Fine Art. Already in Judith Showing the Head of Holofernes (1929), the biblical subject is laced with occult undertones, a signal of the subversive path ahead. Her early costume designs for The Bird of Hermes (c.1926) further hint at the artist’s lifelong engagement with esoteric thought.

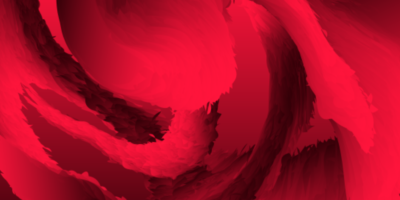

Ithell Colquhoun Alcove 1946 Private Collection © Spire Healthcare, © Noise Abatement Society, © Samaritans

The heart of the exhibition lies in the 1930s and ’40s, when Colquhoun’s dialogue with Surrealism flowered. Botanical reveries such as Water-Flower (1938) demonstrate her talent for conjuring the uncanny from the natural world, while the celebrated Scylla (méditerranée) (1938) fuses the female body with landscape in an unsettling, dreamlike metamorphosis. For the first time, visitors can also see her full storyboard for the unmade Surrealist film Bonsoir (1939) — a tantalising glimpse into what might have been.

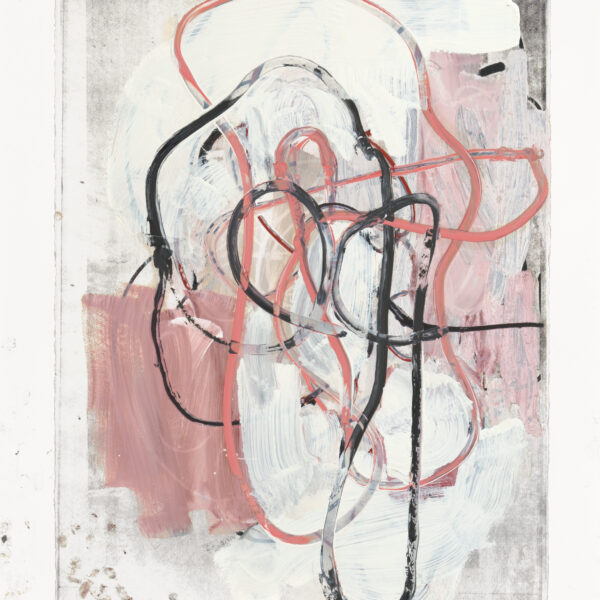

A decisive turning point came through her encounter with automatism. Meeting Gordon Onslow Ford and Roberto Matta in 1939 opened a portal into chance-driven methods of image-making. Works such as Attributes of the Moon (1947) and Gorgon (1946), executed using decalcomania, dissolve the hand of the artist into spectral, otherworldly forms. Paired with their rarely displayed transfer papers, these paintings underscore Colquhoun’s conviction that art could channel the metaphysical rather than merely represent the physical.

From the 1940s onwards, Colquhoun’s practice became increasingly inseparable from occultism. Here, the exhibition excels in showing the depth of her syncretic imagination: The Diagrams of Love (1940–42) braid together alchemy, tantra, and Kabbalah into erotic geometries of union; tesseract diagrams map portals into higher dimensions. Cornwall — with its mythic landscapes and stone circles — provided both subject and spiritual anchor. Paintings like Dance of the Nine Opals (1942) translate the region’s Celtic charge into visionary compositions of rhythm and light.

Attributes of the Moon (1947), ©Tate

The show concludes with Colquhoun’s final experiments: enamel drips and the extraordinary Taro card designs. These late works abandon figuration altogether, distilling her art into pure symbolic force — a shimmering testament to her lifelong quest to merge aesthetic innovation with spiritual inquiry.

If the Surrealist canon has long been dominated by male names, Tate’s retrospective makes a compelling case for Colquhoun’s place within — and beyond — that history. Her work refuses to sit quietly within stylistic categories; instead, it insists on art as a ritual, a journey, and, ultimately, a form of magical knowledge.

This is not simply an exhibition but an initiation. Step inside, and Colquhoun’s cosmos of bodies, landscapes, and other worlds takes hold — a reminder that the boundaries between art and life, flesh and spirit, were for her never fixed, always in flux.

The exhibition is open until 19 October 2025

Header: Ithell Colquhoun, Gorgon, 1946, Private Collection © Spire Healthcare, © Noise Abatement Society, © Samaritans