12 Fragrances: Part 3

The final part of 12 Fragrances – our review of the vital smells that have defined the last 100 years.

neuf / 9

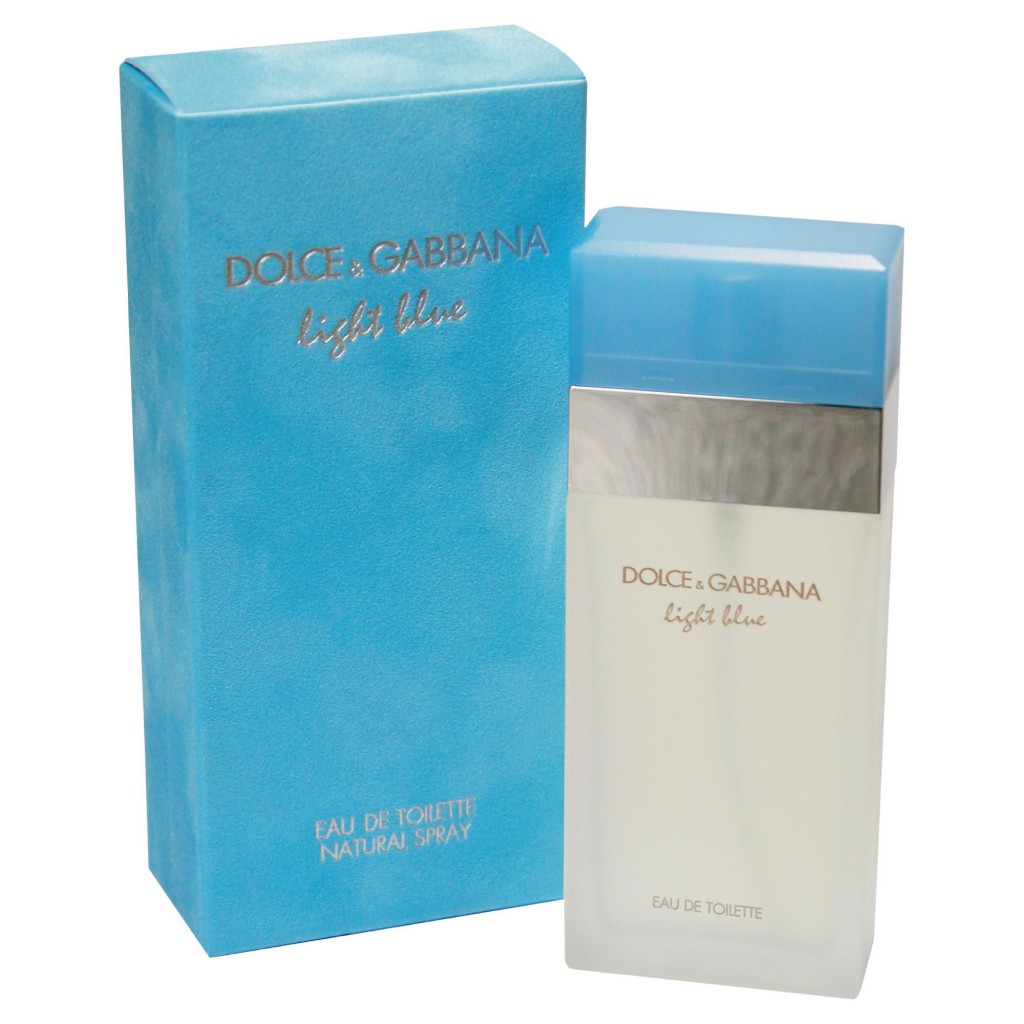

Light Blue / 2001. Designed by Olivier Cresp for Dolce & Gabbana. (P&G)

At this point in Burr’s narrative, you’d be forgiven for thinking that everything that was necessary to say has already been said. Minimalism, then maximalism, then back again; add new ingredient, stir, and leave to settle. And Dolce & Gabbana’s Light Blue – stripped of the David Gandy-heavy advertising – might be perceived to be the weak link in amongst these classic treasures and dated guilty pleasures. It’s a simple fragrance (incredibly, designed by Olivier Cresp, the man who came up with the surreal overload of Angel) which looks back to the freshness of L’Eau d’Issey; but it might as well have been written in another language. Burr calls it ‘Kinetic Sculpture’ – a phrasing that steers close to creating yet another dangerously obscure terminology for fragrance, but which couldn’t be more apt for a craft that’s increasingly becoming a science; where those who study to become master perfumers need a sturdy chemistry grounding first, and therefore see their creations in increasingly molecular terms – as a succession of interacting elements which revolve around each other like a helix as scent gradually dissolves into nothingness. And that notion – of fragrance unravelling over time – has come to form an increasingly tangible part of the very idea of smell.

dix / 10

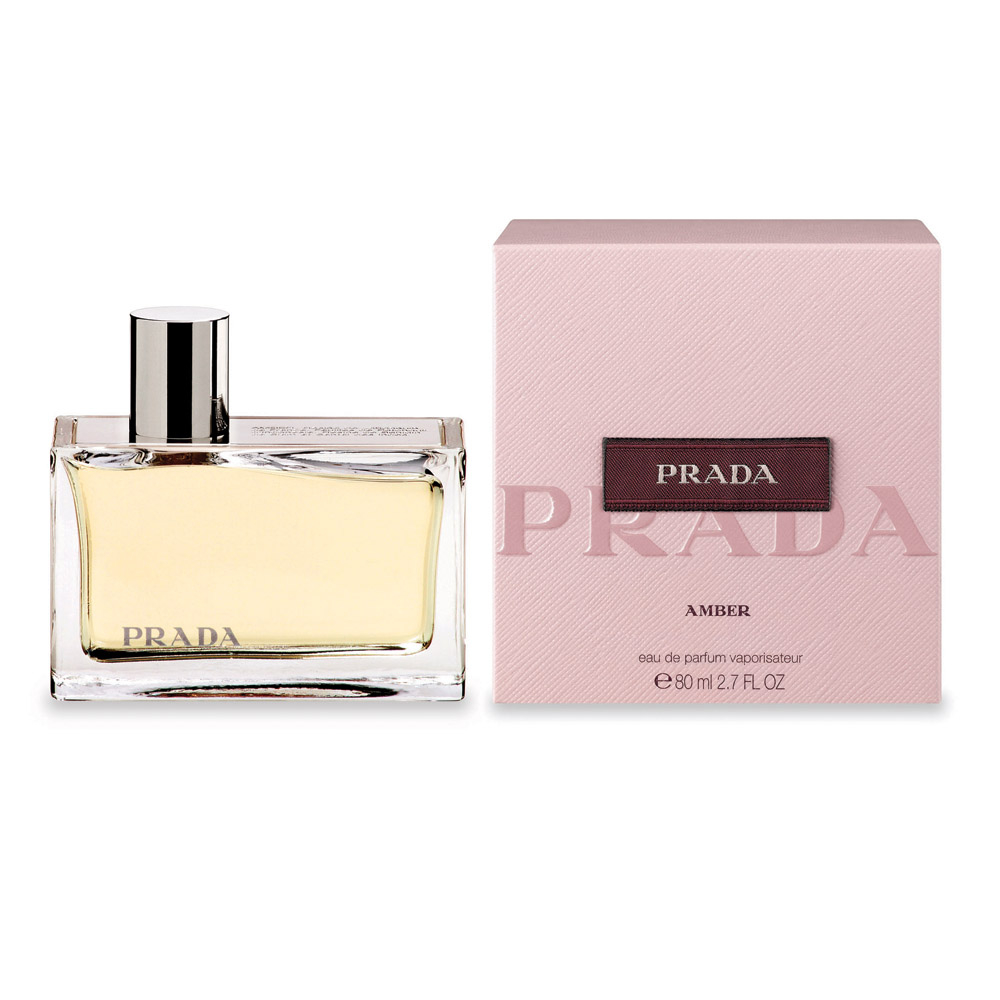

Amber / 2004. Designed by Carlos Benaim, Max Gavarry & ClÃment Gavarry for Prada. (Puig)

Something strange happened at the millennium. Instead of rounding the corner into a perfect new tomorrow, we flipped into reverse. Artisan techniques and timeless craftsmanship became the order of the day – and perfume’s unimpeachably old-school sensibilities enjoyed a dramatic renaissance. It helped that the previous decade’s fascination with brand revival had kick-started a scavenger hunt through the luxury industry’s archives, sniffing out long-lost icons. And it helped, too, that the end of the Nineties had seen the return of the individual perfumer – a mix of niche specialists and maverick blow-ins whose work found a surprisingly substantial audience. So when Miuccia Prada debuted Amber, she was – for once – following a trend. (Although it’s fascinating to think, given how compulsively arbitrary her interests are, how different things might have been had she launched in a different year or season). But it coincided with the zenith of her fascination with romanticism, and so the scent evoked a remembered idea of womanhood, in a bottle anchored with a vintage-style pump diffuser, fronted by a campaign with Daria Werbowy as an ambiguously Hitchcockian heroine. As an expression of the connection between femininity and fragrance, it was less innovation than reclamation; a return to the carnality of scent, touch and skin.

onze / 11

Osmanthe Yunnan / 2004. Designed by Jean-Claude Ellena for Hermès (Hermès Parfums)

Jean-Claude Ellena doesn’t wear fragrance. He lives and breathes it, but doesn’t wear it. And something about that sense of austere remove – probably practical, and maybe even purely pragmatic – filters through to the way he makes his scents. (He’s been memorably described as having caught a ‘severe case of minimalism’, sometime around 1976 – an awkward affliction to catch in the run-up to the Eighties). Ellena has been in-house perfumer for HÃrmes for several years, and in that time has honed the way in which ultra-luxury smells down to a fine art. He labels his work there as a form of haiku – isolating a single scent that recaptures a moment, and paring the fragrance back to representing precisely that. His formulas are short, and focused – a sign of a world where things of extraordinary complexity can be produced with radical test-tube simplicity. But if things are reduced, they’re also stunningly decadent – Ellena’s Osmanthe Yunnan, the fragrance on show in the New York exhibition, will set you back £150. (You could get six bottles of Drakkar Noir for the same price). And alongside Prada’s Amber, Ellena’s scents are proof of our increasing willingness to see perfume revert back towards its’ once spectacularly out-of-reach roots.

douze / 12

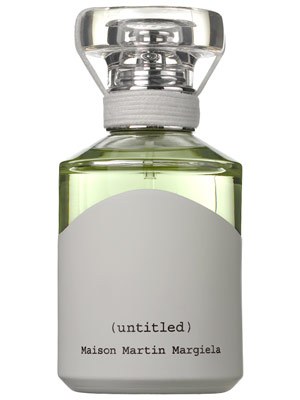

Untitled / 2010. Designed by Daniela Andrier for Maison Martin Margiela

If Burr’s approach is to mirror the course of fragrance with that of art in general, then the perfumes he has chosen reflect their eras in a convincingly specific way. There’s the lush Parisian romance of Jicky (from the same year that spawned the Eiffel Tower and the Moulin Rouge) and the Eighties power-masculinity of Drakkar Noir; the safe mid-century sweetness of L’Interdit alongside the aggressive simplicity of L’Eau d’Issey. And to represent the ‘now’, he’s turned to Daniela Andrier, a once-upon-a-time philosophy student who epitomises the new wave of perfumer-scientists. Andrier is at pains to stress the simplicity of her approach. Memory and chemistry; as straightforward as that. And in the creation of Maison Martin Margiela’s debut perfume, Untitled, she may have found the perfect client and project; a brand synonymous with secrecy on the one hand, and with powerful modernity on the other. The fragrance wears it’s constituents proudly on its’ sleeve, and states precisely what it is, and what it wants to do. Set alongside Jicky (the perfume that once upon a time smelled of the future), it’s indescribably radical; no name, no logo, no mystique. And yet the essentials – water, alcohol, distilled aromas and synthetic additives – remain the same. Memory and chemistry, squared.