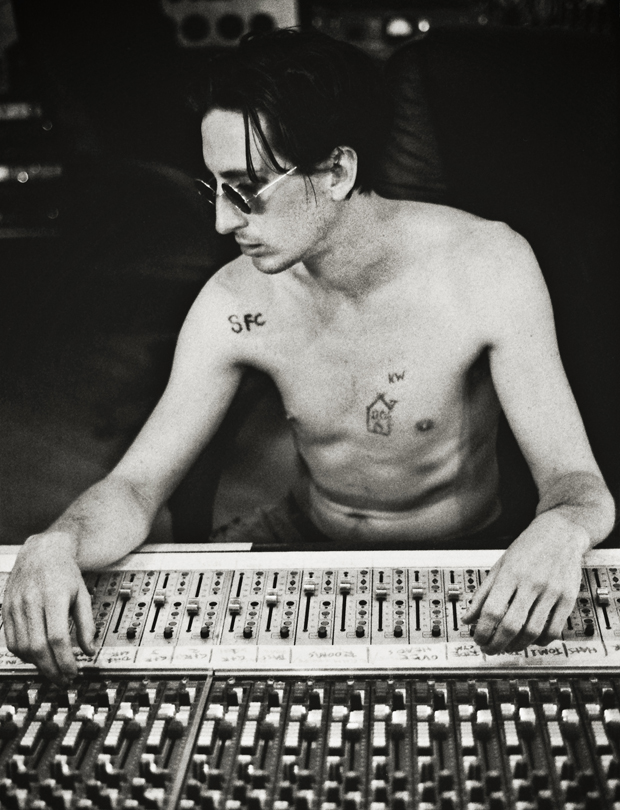

Inteview – Kirin J Callinan: Deep Man

Charlie Clarkson delves into the dark, beautiful world of Kirin J Callinan and finds much more than she bargained for.

DEEP MAN

It can take anything from three minutes to three seconds to judge someone new. A smile, a frown, their clothing or tone of voice are all scrutinised in an instant – willingly or not. But judging a musician is different. We depend on live performances, interviews, or an album to influence our opinion.

A three-minute listen to Kirin J Callinan’s debut LP ‘Embracism’ would raise the expectation of a man held together like a rock. Words like ‘angry’, or ‘pessimistic’, may spring to mind as psychological judgement draws unfounded parallels between man and music.

But in a room melting beneath a sun that poured heat through bolted windows, the man who walks towards me seems apprehensive, almost reticent. Standing indecisively, he tentatively shakes my hand as a slow, barely audible Australian drawl escapes from his mouth to greet me. “H-hi. Hello.” It’s been three seconds. I think that by now, it’s possible he’s judging me here too.

Perhaps we are so quick to judge because we fear what we do not understand. Fast thinking is a defensive reaction to the unfamiliar, but more often than not it creates definitions of people that are usually highly inaccurate reflections of their actual personality. Before me, hesitant and spindly with eyes like troubled pools, Callinan was far from the man I had pictured. My equating of angst-ridden record = angst-ridden musician fell away at the sight of a reserved man who asked if it was okay to sit down. By now, the record, with its destructive guitar riffs and self-degenerations seemed to have been created by another man entirely.

He stared with a wide-eyed curiosity, before gazing out of the window as if to seek the answers to questions I hadn’t yet begun to ask. The last time Callinan was in London, he was “broke, in a band [he] didn’t like, living off a bagel a day, sleeping on a basement floor, suicidal depressive.” Now, five years later, he has been picked up by XL Recordings as a solo-artist, working with a strong team of people who believe in him.

“Coming here for the first time, as a young, very open person, it felt really oppressive, heavy and miserable. I didn’t have my guard up at all. I really took it all on. I was only here for about five weeks, but I was deep in it. This time,” – he pauses to smile – “this time, it’s great, being here with more purpose.”

Growing up in Sydney, Callinan took to the guitar after experimenting with pedals and synthesizers brought home by his father. He speaks affectionately and at great length about his hometown – and Australia as a whole – owing the beginnings of his musical endeavours to both his environment and his dad.

“My dad would play a lot of records, and although I just wanted to listen to speed metal as a teenager, as I got older, I started re-discovering all this strange stuff I was exposed to as a kid. But I’m never thinking that I want to sound like something specific. Still, there’s a hardness, a tough, masculine thing that’s directly related to metal that maybe carries through to my music.”

That vocally haunting toughness has been replaced in conversation by a softer, almost sorrowful spoken voice, heavy with the demands of verbally expressing thought and feeling. “I’m not a trained singer,” Callinan points out. “I have a bizarre timbre in my voice I guess, but it’s not really about hitting the notes perfectly – it’s more about telling a story or expressing an idea.”

The ideas expressed throughout ‘Embracism’ are anchored in the depths of human experience, thriving off an instinctive velocity that pushes the record into the realm of audible emotion. “Aesthetically, the sounds are strange,” Callinan admits. “Conceptually as well. It comes from a unique place and perspective.”

Rich with subplots and subtle concepts, it tunnels far deeper into the self than we would at first find comfortable. It exists not as brutal sadism, but as “a really bizarre creature” that lives off a relationship with – and sometimes, at the expense of – oneself.

As I ask more about the record, he straightens up, realigning himself on the sofa, and a distinct expression takes hold. It is an expression often unknowingly worn by someone who understands what things are like underneath what people hope they are.

“I find it hard to listen to,” he says. “It’s very personal. It was hard to be singing these things over and over again, on the one hand because it’s painful, but then more realistically, you lose the connection with what you’re singing about the more you do it.” He pauses. “It’s hard to find that expressive place – that it came from in the first place – after that.”

Absorbed in his thoughts, I hesitate, wondering how – and when – to best pursue probing what appears to be the result of overwhelmingly intense self-reflection. Delicately, I ask how he feels now, having listened back to the record. His answer is an almost ironic mirroring of my three-minute judgement. “I didn’t realise until recently, but it’s really aggressive,” he laughs. “I thought it was soft and easy, but now I don’t think they’re two words that go with it.”

Recorded and mixed between June of last year and February, Callinan claims ‘Embracism’ to be something he has been making his whole life. “It sounds pretentious, but really I had the luxury of having a huge collection of songs I’d written over many years with lots of ideas to choose from. Having played in lots of different bands, a lot of these songs existed. I might have written them years ago, or performed them live in a largely improvised context, but now I’ve made a definitive version.”

But this didn’t make the process any easier. “It was a highly traumatic experience – I found myself getting pretty moralistic about what I was potentially putting into the world and then had to remind myself that…” He retreats, beginning again with a tone of seriousness. “You get in your head a bit. But you have to commit to things. Sometimes, it’s difficult.”

Like most musicians, Callinan felt concerned if this was a record he really wanted to be making. “I realised all my favourite music is really sleek and polished, of the highest calibre, so why would I want to aim any lower than that?”

A rhetorical question, of course, but ‘Embracism’ isn’t the generically auto-tuned ‘sleek and polished’ we have come to understand as embodied in the pop world. Because what tends to happen when anyone looks too deep into themselves is a manic discovery of elements that can’t and won’t fit together, crying out for resolution. Callinan unearths and mirrors this emotion with a blurred but refined opacity.

Yes, ‘Embracism’ is wild. It purges and praises – often in the same song. It sometimes goes, well, batshit. It is as far from the smooth stereotype of ‘perfection’ as you could possibly go without coming full circle. A deeply personal exposure of memories and dreams, of failure and fear and fear of failure, it is somehow still focused and purposeful. It stands as a defiant testament to refuge and liberation, a fierce declaration of realism, and people in conflict with themselves and their experiences.

Filled with decisive paradoxes, you encounter the unfamiliar in the familiar, or else the familiar at the heart of the unfamiliar. Strangeness and mystery are merged like a riddle wrapped in an enigma. “It’s a mystery, what you’re making – you have an idea, but things always have a life of their own, and that’s what’s exciting. If I understood it, completely understood it, it wouldn’t be exciting anymore.”

So perhaps the unfamiliar doesn’t have to be an unsettling cause for hasty judgement; more often than not, it acts as an exhilarating invitation to discover the old with new eyes, or refresh old eyes with the new. “I’d just like listeners to be invited into the world of the record – they can feel whatever they want to feel.” Pausing momentarily, he rephrases. “It’d be nice if it applies to their own experiences in life, but I don’t want it to be a literal interpretation”

Still, ‘Embracism’ is, in some ways, a literal interpretation of life – an authentic example of all the incessant, painful struggles; of how nothing worthwhile is ever done quickly and with ease; that everything has to suffer from hundreds and thousands of setbacks, tearings, correctings, rebuildings, whilst a frustrating uncertainty lingers beside all our fumbling attempts to embrace it all.

“It’s like a film really, where there are characters and a world and some sort of plot and imagery and different casts play their different roles and there are different sentiments. I hope people accept my invitation into that world.”

Though we may always be a little apprehensive about the unfamiliar, first impressions shouldn’t be made permanent. Accept this invitation; it’s one hell of a world.

WORDS / Charlie Clarkson

PHOTOS / Mclean Stephenson