Out of the Calabash | Goodman Gallery

Winston Branch’s inaugural exhibition with Goodman Gallery in London, Out of the Calabash, marks a quietly significant moment in a career that has long unfolded across multiple geographies and histories without settling comfortably into any single narrative. Presenting a new body of abstract paintings, the exhibition foregrounds Branch’s sustained engagement with colour, light, and spatial openness, while also signalling a subtle but decisive shift in his painterly language.

Returning to large-scale painting for the first time in several years, Branch’s recent works feel markedly lighter than their predecessors. Where earlier paintings carried a dense, worked surface—paint layered and reworked to build depth and resistance—these new canvases open themselves across the plane. Marks are allowed to breathe. Colour moves with a sense of release rather than accumulation. The effect is not one of simplification, but of recalibration: an artist loosening the grip of control in favour of expansion.

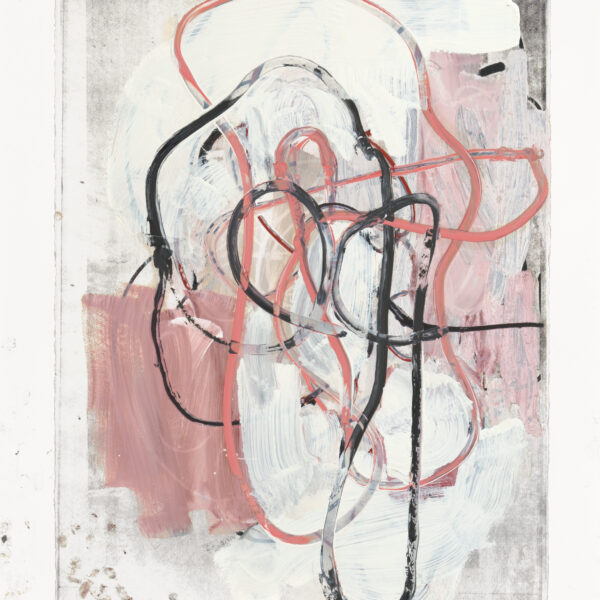

This change in orientation is especially evident in the handling of gesture. Branch’s paintings of the 1980s and 1990s were characterised by compressed, energetic mark-making, short strokes that generated intensity through repetition and friction. In contrast, the works on view here rely on larger, more dynamic brushstrokes that traverse the canvas with confidence. These marks do not seek to define form so much as to activate space, producing a sense of movement that feels bodily rather than illustrative.

Branch’s process remains central to the work’s impact. Frequently working with the canvas laid flat on the floor, he engages the surface with his entire body, collapsing traditional hierarchies of composition. In Today is not a surprise (2023), acrylic paint lands assertively: dark pigment pools along the upper edge of the canvas, countered by softer pink swathes that drift irregularly across the surface. Elsewhere, particularly in several untitled works from 2023, colours bleed and bloom into one another, creating organic transitions that resist containment.

Colour, for Branch, has never been merely formal. His notion of what he calls “the humanity of colour” is palpable throughout the exhibition. These paintings pulse with warmth and energy, not as expressionist outbursts but as sustained atmospheres. Light appears less as illumination than as condition—something the colour carries within it, shaping the emotional temperature of the work.

Seen in the context of Branch’s extensive biography, Out of the Calabash gains additional resonance. Born in Saint Lucia and arriving in Britain as a child, Branch came of age in London during a period of intense cultural cross-pollination, studying at the Slade under figures such as Frank Auerbach and Euan Uglow while absorbing the experimental energies of the city’s countercultural scene. His subsequent movements—across Europe, the United States, and the Caribbean—are not anecdotal footnotes but formative forces that have shaped his visual language.

Branch’s participation in landmark international exhibitions, from the First Pan-African Cultural Festival in Algiers in 1969 to FESTAC ’77 in Lagos, situates his abstraction within a broader political and cultural framework. His turn toward abstraction in the early 1980s coincided with a rejection of the cool detachment associated with conceptual and minimalist practices, favouring instead a mode of painting charged with energy, joy, and presence. That impulse remains visible here, though tempered by experience and restraint.

The exhibition also invites reflection on Branch’s relative marginalisation within dominant accounts of British abstraction, despite his centrality to its development and his longstanding institutional recognition. His ability to operate both within the British art establishment and across the Global South complicates easy categorisation, resisting the narrow frames through which modernist legacies are often viewed.

Out of the Calabash does not attempt to summarise Winston Branch’s career. Instead, it offers a painter still attentive to possibility—testing how colour behaves, how space opens, and how abstraction might continue to carry lived experience without recourse to representation. In its openness and confidence, the exhibition affirms Branch not as a historical corrective, but as a painter whose work remains insistently, productively alive.