Emily Kam Kngwarray | Tate Modern

Tate Modern has opened Europe’s first major exhibition devoted to Emily Kam Kngwarray (1914–1996), one of the most remarkable voices in contemporary art.

A senior Anmatyerr woman from the Sandover region of Australia’s Northern Territory, Kngwarray transformed the ceremonial and spiritual knowledge of her ancestral Country, Alhalker, into an extraordinary body of work that continues to resonate across continents.

Though she only began painting in her seventies, Kngwarray’s late-blooming career was anything but modest. Her vast canvases and batik textiles redefined how Aboriginal art was received internationally, placing her among the most celebrated artists of the late 20th century. Organised in collaboration with the National Gallery of Australia, Tate’s survey brings together more than 70 works, many leaving Australia for the very first time, offering European audiences a rare opportunity to encounter her vision on this scale.

Kngwarray’s art was rooted in lived experience: the intimate rituals of women’s ceremonial practices, the tactile rhythms of preparing food, or the storytelling gestures of drawing in sand. Sitting on the ground to paint, she worked with the same physicality she brought to everyday life, bridging the domestic and the cosmic. Her paintings are not translations of a Western aesthetic, but rather direct expressions of Country—both physical terrain and spiritual continuum.

The exhibition traces her journey from early batiks of the late 1970s to the monumental acrylics that brought her international acclaim. Works such as Emu Woman (1988) and Ankerr (Emu) (1989) demonstrate her recurring engagement with emu tracks and food sources—symbols of both ecological and cultural significance. The pencil yam, from which she takes her name, recurs as another central motif: roots, seeds, and pathways reimagined in dots, lines, and fields of colour.

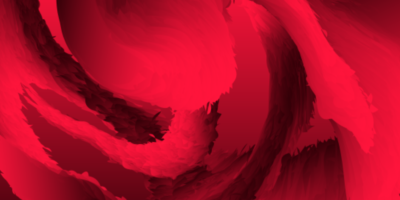

One of the exhibition’s highlights is The Alhalker Suite (1993), a 22-panel masterpiece that attempts nothing less than a portrait of Country itself. With its shifting configurations, it is a work alive to the dynamism of landscape, ceremony, and story, shimmering with pastel pinks, desert blues, and the stippled textures of sand and stone. No single arrangement is definitive, reflecting the living, changing nature of the world she painted.

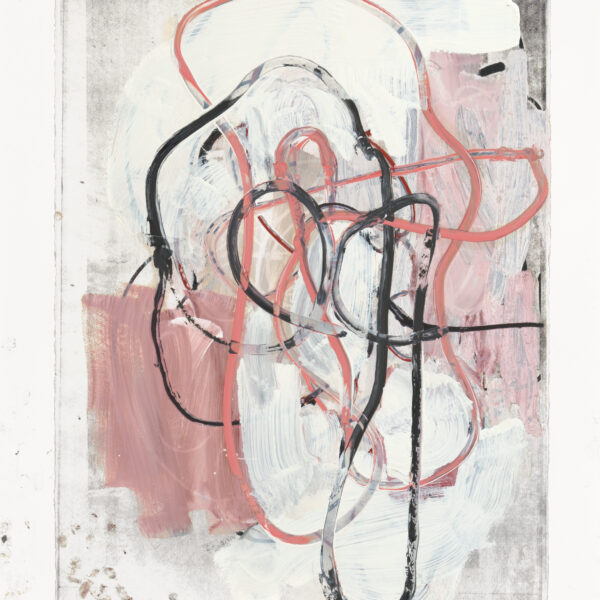

Kngwarray’s late works mark a striking stylistic pivot. Stripped-down parallel lines and bold gestures on white grounds, such as Untitled (Awely) (1994), reveal a tactile immediacy—paint applied with the same intimacy as ochre to skin. Her final canvases, including Yam Awely (1995), return to the intertwining networks of roots, grasses, and pathways, affirming her enduring connection to Alhalker even in her last years.

More than a retrospective, this exhibition positions Kngwarray as a matriarch, innovator, and custodian of Country whose practice remains radically distinct from the Western canon yet conversant with it. Three decades after her death, her art speaks with undiminished vitality—personal, political, ecological, and spiritual all at once.

Tate’s presentation is a long-overdue recognition: not simply of an extraordinary Aboriginal artist, but of a singular modernist whose work insists on new ways of seeing land, life, and art itself.

This summer, Tate Modern will open Europe’s first major exhibition devoted to Emily Kam Kngwarray (c.1914–1996), one of the most remarkable voices in contemporary art. A senior Anmatyerr woman from the Sandover region of Australia’s Northern Territory, Kngwarray transformed the ceremonial and spiritual knowledge of her ancestral Country, Alhalker, into an extraordinary body of work that continues to resonate across continents.

Though she only began painting in her seventies, Kngwarray’s late-blooming career was anything but modest. Her vast canvases and batik textiles redefined how Aboriginal art was received internationally, placing her among the most celebrated artists of the late 20th century. Organised in collaboration with the National Gallery of Australia, Tate’s survey brings together more than 70 works, many leaving Australia for the very first time, offering European audiences a rare opportunity to encounter her vision on this scale.

Kngwarray’s art was rooted in lived experience: the intimate rituals of women’s ceremonial practices, the tactile rhythms of preparing food, or the storytelling gestures of drawing in sand. Sitting on the ground to paint, she worked with the same physicality she brought to everyday life, bridging the domestic and the cosmic. Her paintings are not translations of a Western aesthetic, but rather direct expressions of Country—both physical terrain and spiritual continuum.

The exhibition traces her journey from early batiks of the late 1970s to the monumental acrylics that brought her international acclaim. Works such as Emu Woman (1988) and Ankerr (Emu) (1989) demonstrate her recurring engagement with emu tracks and food sources—symbols of both ecological and cultural significance. The pencil yam, from which she takes her name, recurs as another central motif: roots, seeds, and pathways reimagined in dots, lines, and fields of colour.

One of the exhibition’s highlights is The Alhalker Suite (1993), a 22-panel masterpiece that attempts nothing less than a portrait of Country itself. With its shifting configurations, it is a work alive to the dynamism of landscape, ceremony, and story, shimmering with pastel pinks, desert blues, and the stippled textures of sand and stone. No single arrangement is definitive, reflecting the living, changing nature of the world she painted.

Kngwarray’s late works mark a striking stylistic pivot. Stripped-down parallel lines and bold gestures on white grounds, such as Untitled (Awely) (1994), reveal a tactile immediacy—paint applied with the same intimacy as ochre to skin. Her final canvases, including Yam Awely (1995), return to the intertwining networks of roots, grasses, and pathways, affirming her enduring connection to Alhalker even in her last years.

More than a retrospective, this exhibition positions Kngwarray as a matriarch, innovator, and custodian of Country whose practice remains radically distinct from the Western canon yet conversant with it. Three decades after her death, her art speaks with undiminished vitality—personal, political, ecological, and spiritual all at once.

Tate’s presentation is a long-overdue recognition: not simply of an extraordinary Aboriginal artist, but of a singular modernist whose work insists on new ways of seeing land, life, and art itself.

The exhibition is open to 11 January 2026