Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers

“This inevitability of suffering and despair – anyway, here I am again, recovered for a period – I’m thankful for it.”

– Vincent Van Gogh in a letter to Theo Van Gogh

In the midst of COVID lockdowns, my best friend bought me a 1,000 piece jigsaw puzzle of Sunflowers, arguably one of the most famous and familiar series of Van Gogh’s works. Painstakingly navigating hundreds of pieces with the subtlest differences in yellow, green and ochre, I developed a newfound appreciation for the brushstrokes, subtleties in tone, the layers painted and repainted like the unfolding grasp of visions – and, in truth, a dislike for 4-digit jigsaws.

With a new once-in-a-century exhibition at the National Gallery, you may wonder: what else is there to know about Van Gogh – Starry Night, the infamous self portrait, flowers? But amidst the dark skies, self-reflections and blooms beneath tangled gardens lies a melancholy, syncretism, and a restless search for deep feeling and security.

Poets and Lovers is a breathtaking exhibition that sprawls through 6 rooms, each exploring the complexity of Van Gogh’s densely layered subconscious. Carefully selected and expertly arranged, this collection of loaned and owned works pieces together a narrative that dismantles the reductive tales of bloody ears and asylum walls. Instead, it captures a portrait of the art itself, an experimentation with colour, underlying influences, and the landscapes not only surrounding the artist but within his own mind.

The exhibition opens with works that explore Van Gogh’s poetic sensibilities, weaving together literature and art. Winding green paths stretch toward unseen horizons, trees weep lyrically beneath distorted skies, and lovers find themselves entwined in fleeting moments of intimacy or drifting apart, lost amid fields and shadows.

In Room 3, “The Yellow House: An Artist’s Home”, hangs the famous Van Gogh’s Chair (1888) alongside the achingly mournful Starry Night over the Rhône (1888), a painting transformed into a “poetic subject” by the foreground presence of lovers beneath Ursa Major.

Van Gogh Vincent (1853-1890). Paris, musée d’Orsay. RF 1975 19.

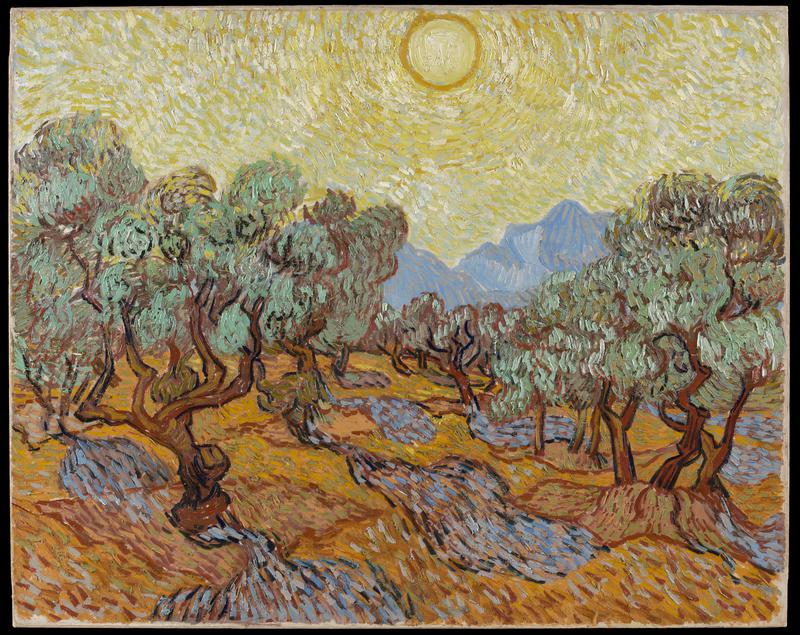

Moving through the rooms, you feel yourself swirling amidst the austere beauty of France. In A Wheatfield, with Cypresses (1889), each intense brushstroke pleadingly vibrates with a fleeting insistence of an inner emotional weight tied down to the very soil. It’s impossible to miss the tension between hope and despair, each balanced precariously in every shade of ochre or cobalt in the curvatures in Mountains at Saint-Remy (1889), or burning under the orb that hovers in Olive Trees (1889). Nature’s consolation is tinged with loneliness, as though his private longing for stability was always just out of reach, the land both consoling and unsettling.

A Wheatfield with Cypresses

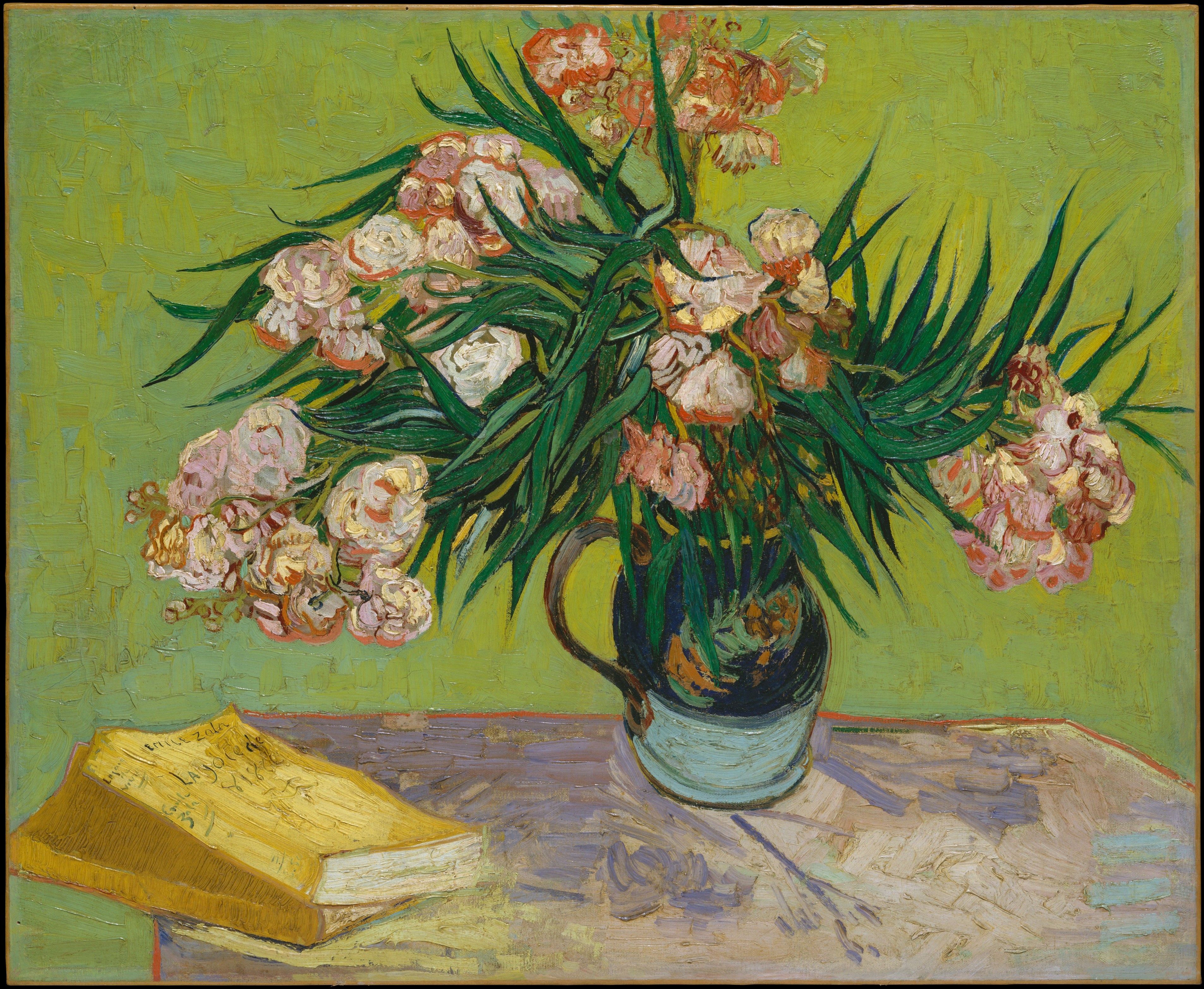

Van Gogh’s deep connection to the land is palpable, his brush capturing not just what he saw but what he felt—an aching reverence for his surroundings as a source of both solace and existential reflection. Symbols littered throughout works further reveal this searching, as in Oleanders (1888) – for Van Gogh, joyous, life-affirming flowers that bloomed “inexhaustibly” and were always “putting out strong new shoots.” Their life is symbolically juxtaposed with Émile Zola’s La joie de vivre, a novel that Van Gogh had placed in contrast to an open Bible in a Nuenen still life of 1885. Significantly, the novel explores the tension between the desire for joy and the crushing weight of human suffering – time itself, fleeting and borrowed.

Oleanders, Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, Zundert 1853–1890 Auvers-sur-Oise), Oil on canvas

Throughout, Van Gogh reinvents himself through style, colour, the landscapes that take on increasingly surreal forms. At the same time, the way we have grown accustomed to understanding Van Gogh transforms into a new way of seeing. These masterpieces are works of art in its most unwavering form – an embodiment of and connection with poets, writers, artists and lovers. This is Van Gogh, a man at once seeking the divine and surrendering to the darkness.

It is a ferocious but tender collection of raw human experience and vision that leaves you with an ache and joy. Emerging from this world, you carry with you the residue of its intensity, like the lingering scent of rain-soaked earth.

Olive Trees, 1889

As you step back into the bustling square, the world feels diminished, the grey London light a jarring contrast to the meditative vistas of emotion. I found myself longing to hold onto the vividness of his vision, the distilled poetics within his paintings, and the fleeting, fragile beauty he so desperately sought to preserve.

On the back of my ticket I wrote: to live fully is to feel the exquisite ache of the universe in every touch, every colour, every fleeting moment.

Perhaps someday, I’ll turn it into a jigsaw.

The unmissable “Poets and Lovers” is open till 19 January 2025 at The National Gallery, London