12 Fragrances: Part 2

12 Fragrances is our review of the vital smells that have defined the last 100 years.

cinq / 5

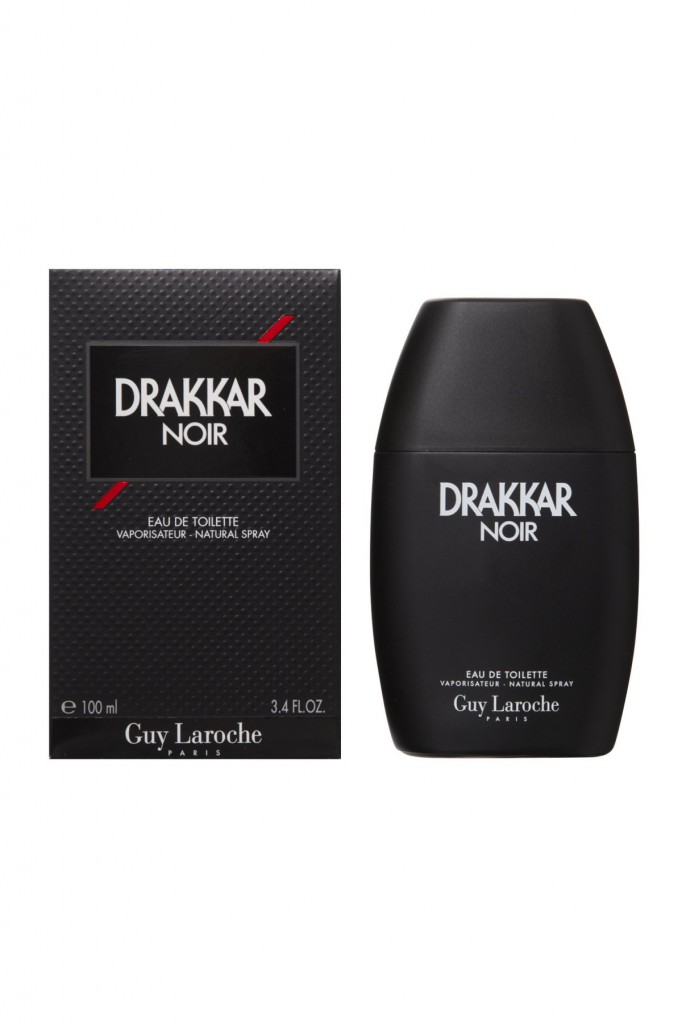

Drakkar Noir / 1982. Designed by Pierre Wargnye for Guy Laroche, 1982

Dihydromyrcenol first surfaced in the mid Seventies; a cheap, powerful new component that smelled citrus-fresh on a near-nuclear scale, and seemed destined for the world of washing-up liquids and industrial cleaning products. But it found its way into the formula for Drakkar Noir, the fragrance Pierre Wargnye created for Guy Laroche, and – Wham! (pun intended) – the Eighties had arrived. It revved Laroche’s name back into the spotlight (he’d had a fashion house for a quarter-century by then), and raced to international bestseller status. Now, it’s brilliantly, spectacularly dated: alongside Old Spice, Kouros and Brut, it’s become a byword for a time when masculinity was spelt out in sky-high lettering, and colognes were things pumped full of uncompromisingly powerful ingredients. Fittingly, it lives on mainly in pulp crime novels, where stubbled heroes with troubled pasts come pre-dipped in the stuff, sweeping suddenly-helpless lady detectives off their feet (if not knocking them unconscious), and luring them to spectacular multi-storey orgasms between satin sheets. One recent online reviewer memorably described it as the scent of ‘a beer-gutted ex jock in stonewashed jeans’ ; a fitting epitaph for a decade whose excess outstayed its’ welcome long ago, and a reminder of how expiration dates work – in more ways than one.

six / 6

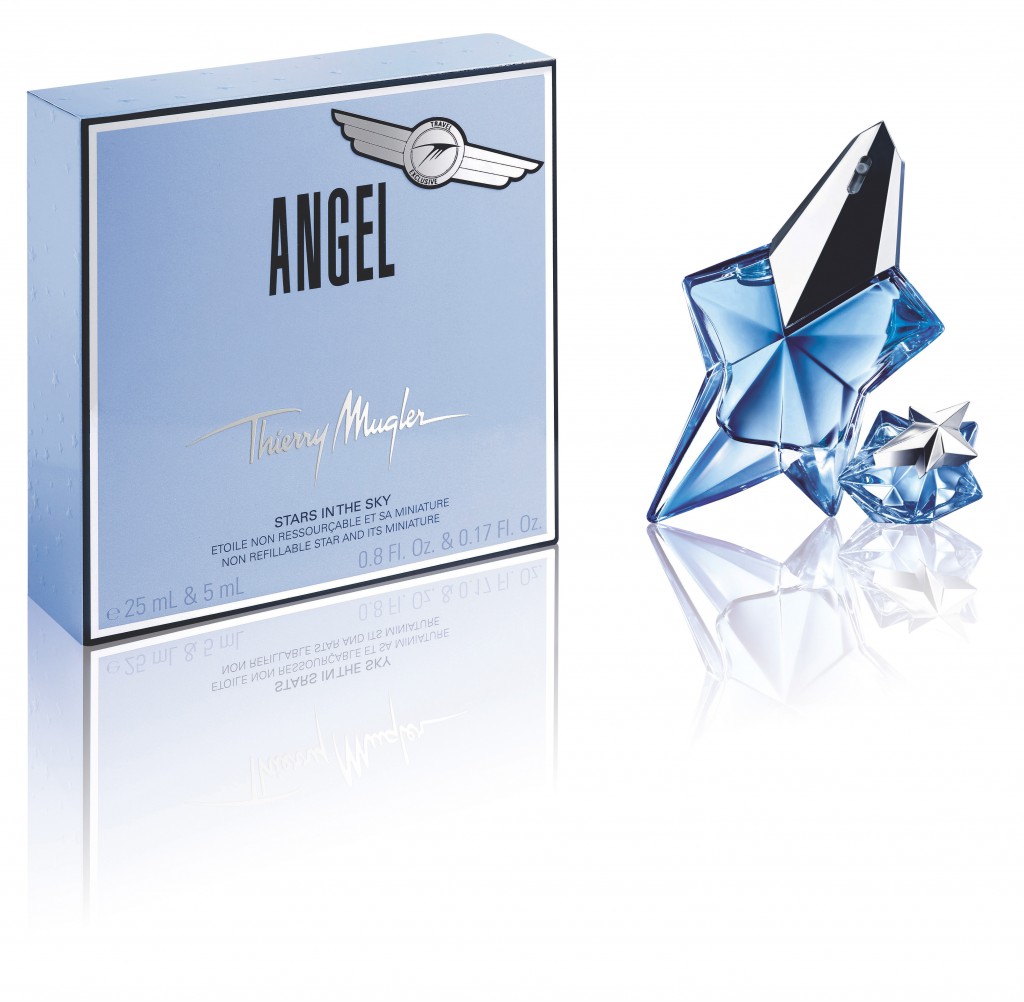

Angel / 1992. Designed by Olivier Cresp & Yves de Chiris. (Clarins Fragrance Group)

In 1967, The Baker’s Digest proudly proclaimed the arrival of ethyl maltol, a ‘potent new flavour enhancer for use in sweet carbohydrate foods’. As another over-excited contemporary writer put it, ‘Fruit tastes are fruitier. Tomato tastes tomato-ier. Mint tastes mintier. Chocolate chocolatier’. The Willy Wonka descriptions aren’t far wide of the mark; it made everything stronger, turning subtle aromas into technicolour and jacking up intensities several times over. But it took wenty-five years for someone to inject the compound into a fine fragrance. And when Olivier Cresp and Yves de Chiris whacked a ton of it in to Thierry Mugler’s Angel, the anti-minimalist perfume was born. Everything about Angel was wrong – the violent kaleidoscope of ingredients, the brief (to capture the childish sweetness of cotton-candy), the jagged star-shaped bottle – and when you put it alongside Miyake’s scent from the same year it seems wildly out of sync with the times. Focus groups hated it. And it came out just as Mugler’s own star was starting to definitively wane. But against all the odds it worked – and has become a monstre to rival Chanel No. 5. And yet (unlike Chanel) it’s not something which has taken to replication; just a strange, stunning anomaly of smell and sensation.

sept / 7

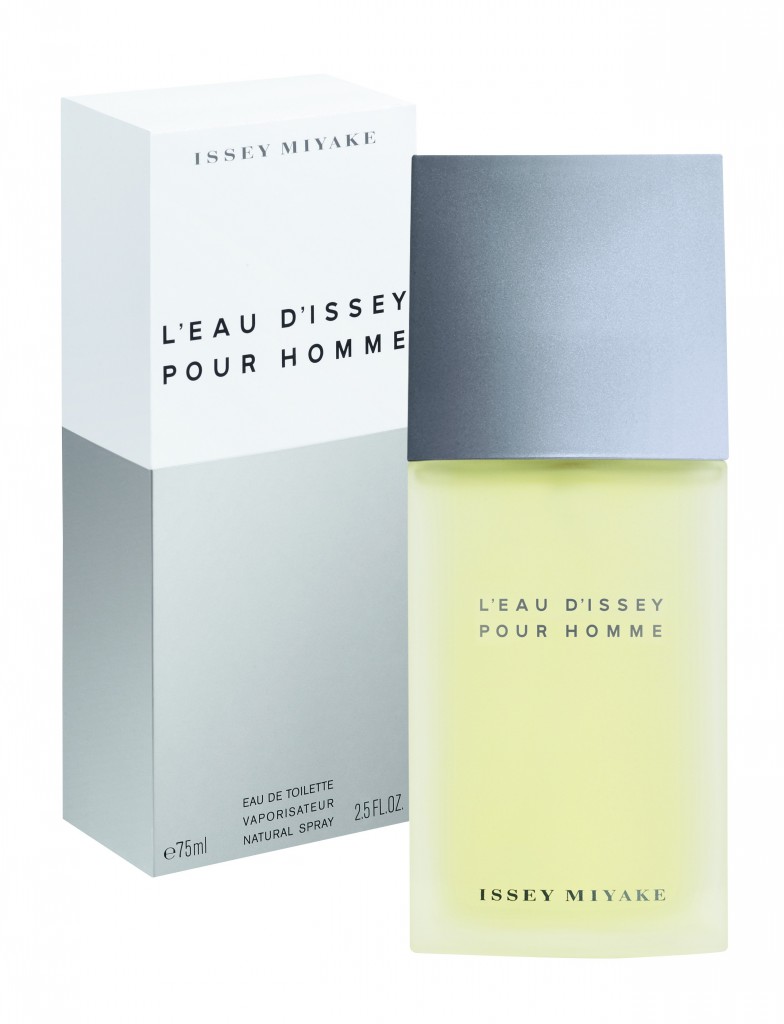

L’Eau d’Issey, 1992. Designed by Jacques Cavallier for Issey Miyake. (Beautà Prestige International)

Someone once wrote that Natasha Bedingfield wasn’t the best singer to emerge in 2004 – but that, in years to come, her breezy pop songs would be the thing that 2004 would most sound like. If that’s the case, then 1992 sounded like Nirvana, and it smelled like L’Eau d’Issey. Miyake’s brief to then-novice perfumer Jacques Cavallier was both clear-cut and contrary: he wanted something that smelled like water. Instead, Cavallier created a fragrance that smelled like the idea of water. It boiled down, largely, to something called Calone 195, and it it provided the dose of bracing ocean-spray intensity that blasted its’ way through Davidoff’s Cool Water and Calvin Klein’s Escape at around the same time. Suddenly everything else that had come before smelled cloying and laboured, faced with the unabashed freshness of these newcomers in their frosted bottles and muted grayscale boxes. It changed both what men smelled like, and more fundamentally what men was suddenly meant to smell like: something clean, and clear, and wholesome, and – ironically, given its’ carefully crafted laboratory formulation – ‘natural’. Which, in a decade which would rise and fall on the twin mantras of grunge and minimalism (both seductively effortless, both desperately contrived) would prove critical – and commercially spectacular.

huit / 8

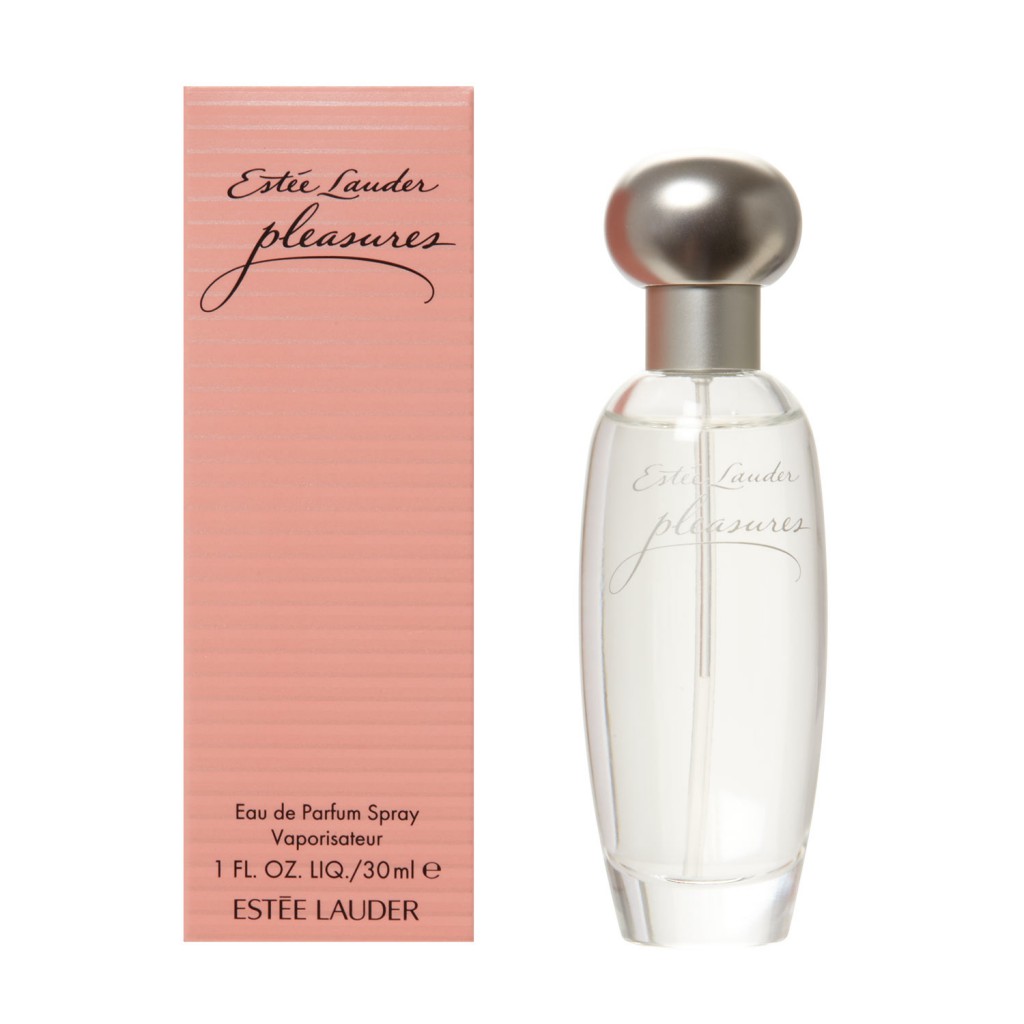

Pleasures / 1995. Designed by Annie Buzantian & Alberto Morillas for EstÃe Lauder (EstÃe Lauder Group)

If there’s anything that you think of when you look at Estee Lauder’s Pleasures ads, filled with long grasses and wildflowers and Liz Hurley hugging puppies in a fluffy pink twinset, carbon dioxide is unlikely to be done of them. And yet Pleasures has rightly become seen a revolutionary tipping point in the modern perfume’s history. The carbon dioxide extraction process it utilised – the soullessly-titled Supercritical Fluid Extraction system – has become one of the industry’s great recent innovations, providing an efficient and stable new way to isolate precious ingredients. And beyond the gentle lure of all that grass and flowers and puppies, there’s a powerful sensation of softness and purity which cuts deep into America’s puritanical fascination with hygiene – the same simplicity which fuels the whole industry of products which ‘smell’ unscented. Pleasures became a runaway success by smelling, in the strangest possible way, of nothing – of being clean, of fresh skin scrubbed with delicate soap. And it touches on one of the dichotomies of fine fragrance; its’ complicated relationship with the far-less-glamorous world of cleaning products, and with underlying cultural ideas about the smell of cleanness -ideas which over a century have gone from coal-tar muscle to citrus-scented freshness to a filtered, un-tampered-with neutrality.