12 Fragrances: Part 1

12 Fragrances is our review of the vital smells that have defined the last 100 years.

une / 1

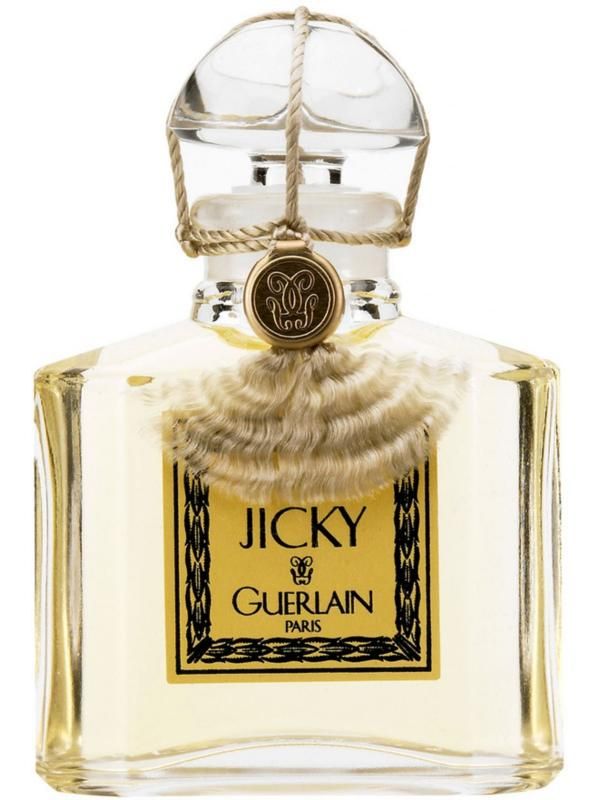

Jicky / 1889. Designed by Aimà Guerlain for Guerlain (LVMH)

As with most histories, what’s less important is whether you were actually first, or simply the first to be remembered. And so Houbigant’s FougÃre Royale has dissolved into the shadows, whilst Aimà Guerlain’s Jicky (eight years younger) has become the star of modern perfume’s origin myth. Before, fragrances had aimed for nothing more than the replication of nature; roses and violets for ladies, sandalwood and amber for gentlemen. But Jicky used coumarin, an aroma which was the industry’s first artificial ingredient, and which did a couple of critical things; it made the product hold its’ scent for longer, and it made it substantially cheaper. Suddenly, perfume went from rarefied luxury to mass-market accessibility – just as the seesaw of elite minority and downtrodden masses was about to be turned on its’ ear for ever. And Jicky – a wild cocktail of the quaint and the cutting edge, with lavender and thyme mashed up with coumarin and other new chemical essences like vanillin and linalool, smelled like the future before it had even arrived. It took decades to really catch on. But when it did, Jicky became an icon, worn by everyone from Sean Connery to Jackie O. You couldn’t get any more schizophrenic – or subversive – if you tried.

deux / 2

No. 5 / 1921. Designed by Ernest Beaux for Chanel (Chanel Parfums)

If they call you le monstre, then you’re either doing something wrong – or something incredibly right. Particularly if you date back to 1921, and to the period which remains perfume’s golden age. Then, the booming New World market, and its’ fascination with Old World luxury, made for an unparalleled intersection of commodity and cash. It allowed France’s only-just-getting-started industry to bloom, melding ingredients which to today’s margin-conscious conglomerates can only seem like a fantasy. Joy, Shalimar, Arpège and Narcisse Noir all exploded into the spotlight, one after the other – and made their way across the Atlantic to an eager new universe of department store counters and drugstore shelves. Chanel’s first fragrance was just another name on the line-up, formulated from a collision of floral extracts and jarringly modern aldehydes. It wasn’t the first designer fragrance out of the blocks – Poiret had already gotten there a decade before – nor was it the first to use aldehydes. But Chanel No. 5 smelled intoxicating and new from the moment it launched, and was instantly and endlessly imitated, long before the fragrance’s myth machine even came into being. And Ernest Beaux’s combination of C10, C11 and C12 compounds has come to define what we say when we mean ‘perfume’.

trois / 3

L’Interdit / 1957. Designed by Fabrice Fabron for Givenchy (LVMH)

Once upon a time, apothecaries concocted one-of-a-kind perfumes for fairytale princesses. By the Fifties, there were precious few princesses (or apothecaries) left in the world – but there were movie stars instead, and Hubert de Givenchy had a readily available princess in the form of Audrey Hepburn. Givenchy’s business and Hepburn’s film career were both only five years old when he commissioned a bespoke fragrance to go with the dark, elegant costumes he was creating for her on screen. The creation of L’Interdit was a pivotal moment in celebrity fragrance; it wasn’t, strictly speaking, a Hepburn endorsed perfume – and Hepburn didn’t see a franc of the profits. But the women bought that scent were buying into Hepburn’s lovably fragile ideal. And Fabrice Fabron simply did what so many other perfumers of the day were doing; he recycled Chanel’s head-spinning mix of aldehydes and flower essences into a far softer, more delicate blend, tuning out the scandalous sexuality in favour of a more Hays Code-friendly bouquet to suit the Fifties’ careful mixture of freshness and closely-guarded virtue. Decades later, Susan Irvine called L’Interdit ‘Chanel No. 5’s daughter’, reiterating the shift in culture between Chanel and Guerlain’s generations – and emphasising perfume’s susceptibility to being rewritten to suit the times.

quatre / 4

Aromatics Elixir / 1971. Designed by Bernard Chant for Clinique (EstÃe Lauder Group)

Like any greatest hits compilation, certain omissions and substitutions in Burr’s selection are always going to be contentious. Rounding the corner from the patchouli haze of the Sixties you expect to see the disco era hove into sight with the slick blue-and-black-banded tube of YSL’s Rive Gauche. Instead, Burr’s chosen the more prosaic Aromatics Elixir; a best-selling product, admittedly, but one confined to Clinique’s concession counters, close to the skincare label’s heartlessly prominent ‘100% Fragrance Free’ signposts. But the Elixir signalled a liberating new era in the most fundamental of ways; in the decade in which New York would become the cultural centre of the world, one of its’ definitive fragrances would be launched, not by a classic French house, but by a Minnesota-born beauty editor called Carol Phillips, who commissioned Bernard Chant (the man behind the equally enduring – and equally American – Aramis) to come up with a signature scent for her fledgling beauty brand. It was the mark of the sea-change in the fragrance industry – an unadvertised, word-of-mouth success which slotted neatly into a Nine To Five-r’s handbag, and which paid little or no deference to previous notions of how a woman should be, or act, or smell. New fragrance, new brand, new world order.